Originally posted on TowardsDataScience.

Introduction

To get intimately familiar with the nuts and bolts of transformers I decided to implement the original architecture in the “Attention is all you need” paper from scratch. I thought I knew everything there was to know, but to my own surprise, I encountered several unexpected implementation details that made me better understand how everything works under the hood.

The goal of this post is not discuss the entire implementation — there are plenty of great resources for that — but to highlight seven things that I found particularly surprising or insightful, and that you might not know about. I will make this concrete by pointing to specific lines in my code using this hyperlink robot 🤖 (try it!). The code should be easy to understand: it’s well documented and automatically unit tested and type checked using Github Actions.

The structure of this post is simple. The first three points revolve around implementing multi-head attention; the last four are about other components. I assume you have conceptual familiarity with the transformer and multi-head attention (if not; a great starting point is the Illustrated Transformer) and kick off with something that helped me tremendously in better understanding the mechanics behind multi-head attention. It’s also the most involved point.

Table of Contents

- Multi-head attention is implemented with one weight matrix

- The dimensionality of the key, query and value vectors is not a hyperparameter

- Scaling in dot-product attention avoids extremely small gradients

- The source embedding, target embedding AND pre-softmax linear share the same weight matrix

- During inference we perform a decoder forward pass for every token; during training we perform a single forward pass for the entire sequence

- Transformers can handle arbitrarily long sequences, in theory

- Transformers are residual streams

Wrapping up

1. Multi-head attention is implemented with one weight matrix

Before we dive into it; recall that for each attention head we need a query, key and value vector for each input token. We then compute attention scores as the softmax over the scaled dot product between one query and all key vectors in the sentence (🤖). The equation below computes an attention-weighted average over all value vectors for each input token at once. Q is the matrix that stacks query vectors for all input tokens; K and V do the same for key and value vectors.

\[Attention(Q,K,V)=softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}})V\]How, then, do we obtain these query, key and value vectors efficiently for all tokens and heads? It turns out we can do this in one go using a single weight matrix W. This is different from the three projection weight matrices one might expect after reading the paper or the Illustrated Transformer. Let’s walk through how this works.

Let’s say that our input consists of 4 tokens: [“hey”, “how”, “are”, “you”], and our embedding size is 512. Ignoring batches for now, let X be the 4x512 matrix stacking token embeddings as rows.

Let W be a weight matrix with 512 rows and 1536 columns. We will now zoom in on this 512x1536 dimensional weight matrix W (🤖) to find out why we need 1536 dimensions and how multiplying it with X results in a matrix P (for projections) that contains all the query, key and value vectors we need. (In the code 🤖 I call this matrix qkv)

The Matrix Multiplication Behind Multi-head Attention

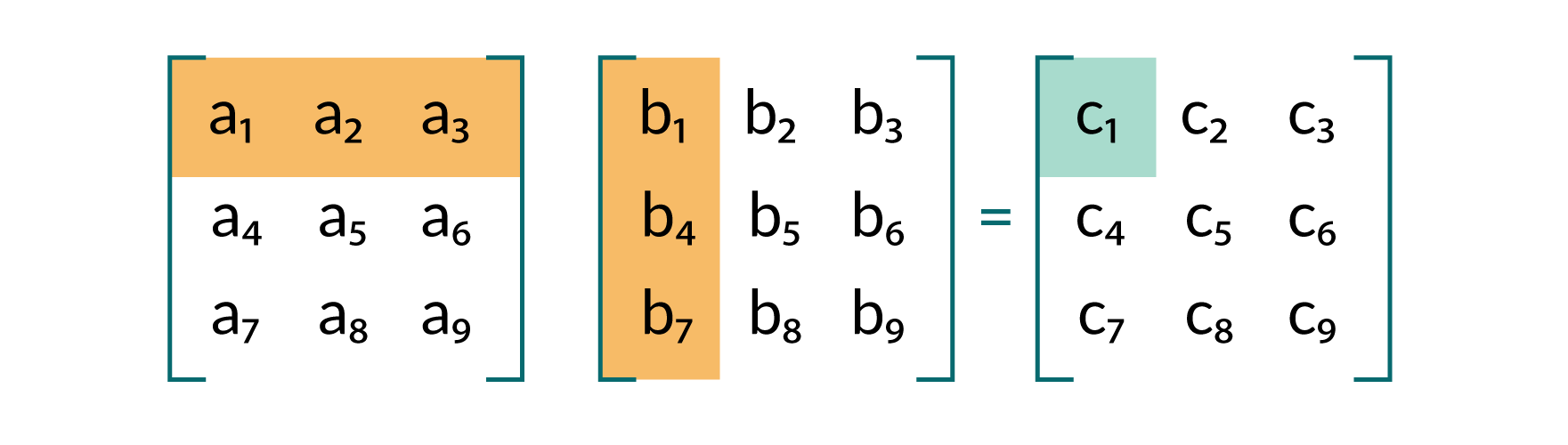

Each element in the resulting 4x1536 matrix P=X@W is the sum of the element-wise product (in other words: the dot product) between a row vector in X (an embedding) and a column vector in W (some weights).

As a refresher on matrix multiplication, the image below visualizes how to compute the first element of a simple 3x3 matrix when multiplying two 3x3 matrices. The same strategy applies to our bigger matrices X and W.

|

|---|

| Example: how to compute the first element in 3x3 matrix multiplication. |

So, each element in the ith row P[i, :] in our projection matrix is a linear combination of the ith token embedding X[i, :] and one of the weight columns in W. This means we can simply stack more columns in our weight matrix W to create more independent linear combinations (scalars) of each token embedding in X. In other words, each element in P is a different scalar “view” or “summary” of a token embedding in X, weighted by a column in W. This is key in understanding how eight “heads” with “query”, “key” and “value” vectors hide within each of P’s rows.

Uncovering attention heads and query, key and value vectors

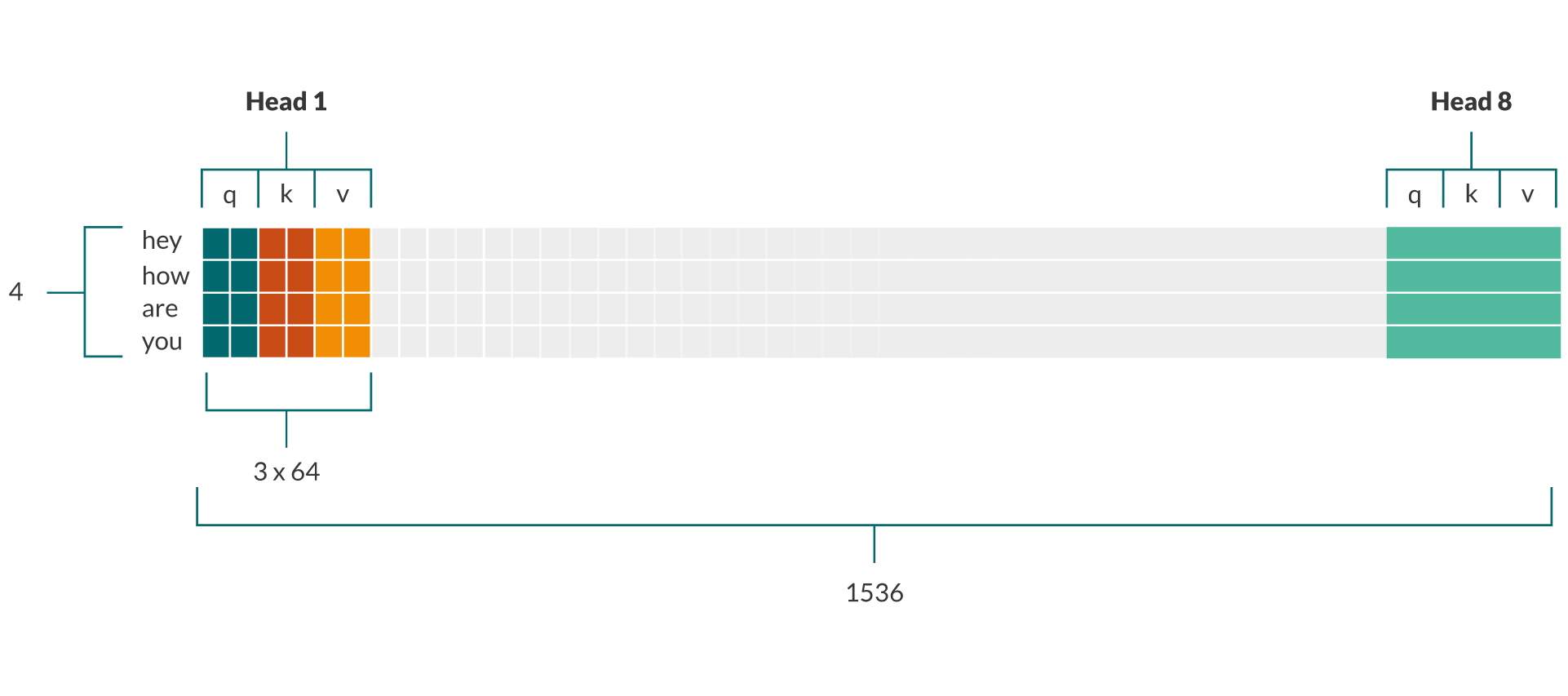

We can decompose the 1536 columns that we have chosen for W (and end up as the number of columns in P) into 1536 = 8 * 3 * 64. We now uncovered eight heads with each three 64-dimensional vectors hiding in every row in P! Each such “vector” or “chunk” consists of 64 different weighted linear combination of a token embedding and we choose to interpret them in a certain way. You can see a visual representation of P and how to decompose it in the image below. The decomposition also happens in code (🤖).

|

|---|

P=X@W contains the query, key and value projections for all heads |

For multiple sentences in a batch, simply imagine a third dimension “behind” P that turns the 2D matrix into 3D matrix.

Encoder-decoder attention

For encoder-decoder attention this is slightly more involved. Recall that encoder-decoder attention allows each decoder to attend to the embeddings outputted by the topmost encoder

For encoder-decoder attention, we need query vectors for the decoder token embeddings, and key and value vectors for the topmost encoder token embeddings. That’s why we split W into two — a 512x512 and a 512x1024 matrix (🤖) — and perform two separate projections: one to obtain the key and value vectors from the encoder’s embeddings (🤖), and one to obtain query vectors for the decoder’s embeddings (🤖).

Finally, note that we do need a second weight matrix (🤖) in multi-head attention to mix the value vectors from each head and obtain a single contextual embedding per token (🤖).

2. The dimensionality of the key, query and value vectors is not a hyperparameter

I never really thought about this, but I always assumed that the dimensionality of the query, key and value vectors was a hyperparameter. As it turns out, it is dynamically set to the number of embedding dimensions divided by the number of heads: qkv_dim = embed_dim/num_heads = 512/8 = 64(🤖).

This seems like a design choice by Vaswani et al. to keep the number of parameters in multi-head attention constant, regardless of the number of heads one chooses. While you might expect the number of parameters to grow with more heads, what actually happens is that the dimensionality of the query, key and value vectors decreases.

If we look at the figure above that shows R=X@W and imagine single-head attention, this becomes clear. The number of elements in X, W, and R remain the same as with eight heads, but the way we interpret the elements in Rchanges. With a single head, we have just one query, key and value projection per token embedding (a row in P) and they would span one third of each row: 512 elements — the same as the embedding size.

What’s the point of multiple heads then, you might wonder? Well, Vaswani et al. argue that it allows heads to capture different “representation subspaces”. For example; one head might track syntactic relations, while another focuses more on positional information. There’s quite some work that investigates whether this indeed happens in practice, e.g. in translation. In fact, I did some work on this myself a few years ago in summarization.

3. Scaling in dot-product attention avoids extremely small gradients

Similar to the previous point, I never really thought about why we divide attention logits by some constant (🤖) but it’s actually pretty straightforward.

Recall that each logit is the result of a dot product (i.e. sum over the element-wise product) between a query and a key vector. A higher number of dimensions qkv_dim thus results in more products in that sum — causing higher variance in attention logits. As we can see in the examples below, a softmax transformation on logits with high variance results in extremely small output probabilities — and therefore tiny gradients.

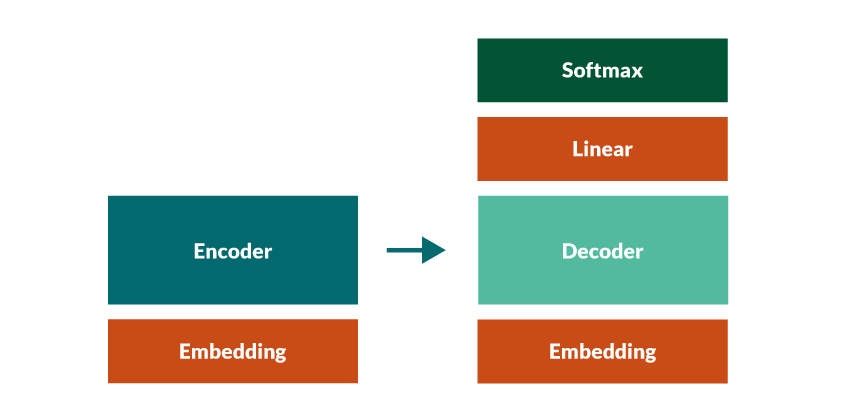

4. The source embedding, target embedding AND pre-softmax linear share the same weight matrix

We now move away from multi head attention and dive into “weight tying” — common practice in sequence to sequence models. I find this quite interesting because embedding weight matrices actually make up for a huge number of parameters relative to the rest of the model. Given a vocabulary of 30k tokens and an embedding size of 512, this matrix contains 15.3 million parameters!

Imagine having three such matrices: one that maps source token indices to embeddings, one that maps target tokens to embeddings, and one that maps each of the decoder’s topmost contextualized token embeddings to logits over the target vocabulary (the pre-softmax linear layer). Yeah; that leaves us with 46 million parameters.

|

|---|

| Weight tying: the three red blocks share the same weight matrix. |

In the code you can see that I initialize one embedding layer in the main transformer class (🤖) that I use as encoder embedding (��), decoder embedding (🤖) and decoder pre-softmax transformation weights (🤖).

5. During inference we perform a decoder forward pass for every token; during training we perform a single forward pass for the entire sequence

This one might be obvious to some — especially those working on sequence to sequence tasks — but crucial to understanding how a transformer is actually trained.

Inference

Let’s say that we are in inference mode, in which we autoregressively (one by one) predict target tokens. The transformer always outputs a distribution over the vocabulary for each token in the batch. The next token is predicted based on the output distribution of the last token index in the batch (🤖). This means that we basically throw away all the output distributions for all the previous indices.

Training and Teacher Forcing

This contrasts training in which we use teacher forcing. During training, we perform just one forward pass through the decoder, regardless of the sequence length (🤖). We (the teacher) force-feed the entire batch of ground-truth target sequences, at once. This gives us all next-token predictions at once, for which we compute the average loss.

Note that each token prediction is based on previous ground-truth tokens and not previously predicted tokens! Note also that this single forward pass is equivalent to autoregressive decoding using only ground-truth tokens as input and ignoring previous predictions (!), but much more efficient. We use an attention mask to restrict the decoder self-attention module to attend to future tokens (the labels) and cheat.

I think it’s useful to realize that this way of training, called teacher forcing, is applied not only to translation models, but also to most popular pre-trained autoregressive language models like GPT-3.

6. Transformers can handle arbitrarily long sequences, in theory…

…in practice, however, multi-head attention has compute and memory requirements that limit the sequence length to around 512 tokens. Models like BERT do, in fact, impose a hard limit on the input sequence length because they use learned embeddings instead of the sinusoid encoding. These learned positionalembeddings are similar to token embeddings, and similarly work only for a pre-defined set of positions up to some number (e.g. 512 for BERT).

7. Transformers are residual streams

On to the final point. I like to think of a transformer as multiple “residual streams”. This is similar to how an LSTM keeps a left-to-right, horizontal “memory stream” while processing new tokens one by one, and regulates information flow with gates.

In a transformer, this stream doesn’t run horizontally across tokens, but vertically across layers (e.g. encoders) and sub-layers (i.e. multi-head attention and fully connected layers). Each sub-layer simply adds information to the residual stream using residual connections. This is an awesome blogpost that discusses residual streams in more detail, and this is a cool paper that exploits the notion of “vertical recurrence”.

A consequence of this residual stream is that the number of dimensions of intermediate token representations must be the same throughout all (sub-)layers, because the residual connections add two vectors (example in the encoder: 🤖). On top of that, because the encoder (and similarly decoder) layers are stacked on top of each other, their output shape must match their input shape.

Wrapping up…

Thank you for reading this post! Let me know if you liked it, have questions, or spotted an error. You can message me on Twitter or connect on LinkedIn. Check out my other blogposts at jorisbaan.nl/posts.

Even though I wrote the code to be easily understandable (it’s well documented, unit tested and type checked) please do use the official PyTorch implementation in practice 😁.

Thanks to David Stap for the idea to implement a transformer from scratch, Dennis Ulmer and Elisa Bassignana for feedback on this post, Lucas de Haas for a bug-hunting session and Rosalie Gubbels for creating the visuals. Some great resources I looked at for inspiration are the PyTorch transformer tutorial and implementation; Phillip Lippe’s transformer tutorial; Alexander Rush’s Annotated Transformer and Jay Alammar’s Illustrated Transformer.